Should we train Artificial Intelligence Models as we train kids?

Suppose you want to train a model that recognizer handwritten digits: you define some architectures and algorithms that you want to try, and train them using a set of images associated with the corresponding digit – the training corpus. You then evaluate each model performance, and chose the best one. This is a very typical approach, but it is not the same way we have been trained when we were kids.

With respect to the digit example, the training corpus will be composed of a mix of very well written digits, poorly written digits, some will be very masculine, some very feminine, etc. Classifying some examples will be more difficult than others, not all the examples belongs to the same class of difficulty. What we usually do, with machine learning, is shuffling these examples, and throwing them all together to the model, hoping that it will find its way out.

Suppose that the same approach would have been followed with you when you were a kid: do you think giving you oddly written characters in a disparate order would have been a good way to learn recognizing digits? It’s of course the same with other subjects, you have been trained on doing sums before subtractions and so on, not mixing them together. When we train humans (or animals), we start with some simple tasks and then we increase the complexity, until the student is able to solve difficult problems. This approach is called “Curriculum Learning”.

This week I have read this article, that is precisely on this concept:

Curriculum Learning. Yoshua Bengio, Jérome Louradour, Ronan Collobert, Jason Weston. Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Machine Learning, Montreal, Canada, 2009.

https://ronan.collobert.com/pub/2009_curriculum_icml.pdf

To argument the intuition, the authors start considering the fact that the loss function of a neural network is a non-convex function. This has a precise mathematical definition, but to make the things simpler look at the picture below:

On the left side you have a convex function, it is easy to spot the minimum of this function, at x=0.5. On the right the function is non-convex: you have many local minimums. The problems with these function is that the learning algorithm can be trapped into a local minimum, and do not find another place where the error function has a lower value.

When you train a neural network you start with some initial parameters, and the algorithm should tune them little by little to find the global minimum – the minimum of all the minimums. It has been observed that can be very hard find a good starting point for the training. For this kind of problems a method called “continuation” exists. With this method you do not start immediately optimizing on the very complicated target function, but you first start on a more simple one. Once you find a minimum for the simpler one, you use this minimum as starting point for the next part of the training.

To say it in a more mathematical language, you introduce a parameter λ whose value can be between 0 and 1. When λ is zero, you work on a very simplified problem, when λ is 1 you work on the target problem – the very complex one. You arbitrarily decide how many steps you want to introduce: suppose you just have λ=0 or λ=1, for simplicity. You then take your corpus and you assign some of the examples to the set with λ=0 and the others to the set with λ=1.

In this way you are creating some “classes”. The model will have to graduate on class λ=0 before going to the next level, a bit like at school. You may think that it is difficult to introduce this classification in your corpus: but maybe you can find some measure that helps understanding the example difficulty, and do the repartitioning in classes automatically. You could also decide that some input parameters are for sure relevant, and some others may be relevant – and then trains first the model with less inputs introducing later the others (the lower the λ is, the more input parameters are turned to zero).

The authors make an example training a neural network to recognize images with ellipses, triangles and rectangles. They first generated a corpus only with circles, squares and equilateral triangles. The more complex pictures are introduced later, along with less contrasted backgrounds. Another experiment is with Wikipedia’s phrases: you want to build a model that predict the next word knowing the previous s words, for instance s=5. First you start training a model that works only with the 5000 most common English words, then you train it again with the 10’000 most common words and so on.

What are the benefits in the end? In theirs experiments the authors have found that the models trained with curriculum learning perform better in the test phase – they are more probably less over-fitting. The training speed has also been improved, because the learner wastes less time with noisy or harder examples. There is no bulletproof strategy to split the training into classes – but this is too much to ask to a single article, and is very debatable subject even on humans: what should you teach in first grade to a kid? The article dates of 2009 – there is probably much more to know on this subject if you are interested.

The Neural Logic Machines

A neuro-symbolic model able to learn on its own first-order logic relations and solve some interesting problems, like sorting an array or the block world puzzle.

As promised, this week I have read:

Dong, Honghua and Mao, Jiayuan and Lin, Tian and Wang, Chong and Li, Lihong and Zhou, Denny,

Neural Logic Machines

Seventh International Conference on Learning Representations. https://iclr.cc/Conferences/2019/Schedule

https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.1904.11694

Compared to other papers I have read, I have found it both very clear and very dense. While reading it I was highlighting every single paragraph, each single piece seemed giving some important or useful information. Even if it is only 22 pages with the bibliography and the appendix, it will be very hard to resume it in one single Sunday morning post; but unfortunately this is the short time I can devote to this activity.

I found this article while reading about Neuro-Symbolic systems, and as it it different from the other examples I have found; I wanted to have a look. Being Neuro-Symbolic, it is a neural network based model that include also some symbolic form of reasoning over the extracted features. Reading the introduction, I see also that the goal is also to have an inductive learning model: you do not program the logic rules, you provide examples and the model extracts the rules on its own! This is very fascinating, but of course it comes with some hard limitations. Notice also that it will extract some rules, but they will be in the form of neural weights and very likely they will not be human interpretable, even tough the rules will be connected with logic operators.

The training of this model has to be similar to the way an human is trained: just because NLM has to extract on its own the rules it is not possible to start with difficult cases. This way of training is called curriculum learning: the examples are organized in a set of levels sorted by complexity. A model to pass a level must reach a certain performance: if it does not reach it, it will be discarded, otherwise it will be kept and continue to the next level. Examples that make a model fail are very useful, the can be kept and added to the training material, so that the next generation will be better trained. Since the architecture is the same, the model instances will be differentiated by the random seed used to initialize them. At the end of the paper, there is a nice table showing that for complex problems it is hard to train a good model, as fewer of them are able to graduate!

The reference problem used for this NLM is the classic “block world”: some object are laid on the ground, some other stacked on top of them; you can move one object only if it has nothing on top of it and you can put it on the ground or on top of another clear object; you have a start configuration and a target configuration to be reached. A kind of problem that can be modeled using first order logic clauses; but remember the Neural Logic Machine (NLM) has to create the rules on its own, just some initial facts will be provided as training input.

Let’s come to the limitations of this model: you have first-order logic (no rules on object sets, just on single instances). It can produce rules with the “exists” or “for all” quantifiers. It cannot produce recursive or cyclic rules. As meta-parameters you have to provide the maximum “arity” of the deduced rules (maximum number of rule parameters) and the maximum number of rules that are used in a computation. These two limits are called Breath and Depth respectively. The authors say NLM “realize Horn clauses in first-order logic”, to know quickly more see for instance https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horn_clause

The computation is carried on using tensors that represent the probability of one relation to be true – so a true relation between object a and b will be represented by 1, while a false one will be represented by a 0. During the calculation these will be real numbers, but will be generated by sigmoids so they should not be too close to 0.5

The initial facts – 1 arity rules – will be represented by a matrix with the size of the number of input objects and the number of the facts. For instance if you have 3 object and the facts being red and being blue you will have a 3×2 matrix.

Binary predicates will be represented by [m, m-1, r] matrices where m is the number of input instances and r is the number of binary relations. This can continue with ternary relations [m, m-1, m-2, r] and so on. The fact is that you do not need oftern high arity relations, usually ternary relations are enough and you do not need a high Breadth model.

From this you find also an important limitation of NLM: they can work with single instances of objects (1 hot encoded) but they cannot work with real valued input: they can reason with distinct objects in the block world but they cannot reason with the heart-rates, pressures, temperatures etc.

Now that is clear that relation values between objects can be represented by tensors [m, m-1,…r], it is time to understand how the computation evolves in the Depth of the model. There are a set of operation that are defined that allow to compose these tensors. The computation is organized in layers. Each layer will be implemented by a muti-layer perceptron: given the m possible objects all the x-arity input combination will be produced and these will be given as input to replicas of the same multi-layer perceptron. Having the same perceptron means that its parameters will be the same in all the replicas, and they will not be too much – like in a convolutional neural network. The “all possible combinations inputs” causes problems: if you have 3 objects a, b and c, and a 2-arity relation you will have to compute it for (a,b), (a,c),(b,c),(b,a),(c,a),(c,b). If you do it with more object you will see that this is a factorial explosion in the combinations. Ok, machine learning models can have billion of parameter, but having something factorial it is something scaring.

In the and all possible inputs to a relation are generated, they pass in parallel in the same neural network and the result is squashed by a sigmoid. The output is ready to be passed to the next level but, there is more to be done. So far we considered only r-arity, but actually the model in a level considers also r-1 and r+1 arities. It is therefore mixing 2-arity rules also with 1-arity and 3-arity when computing one level. In this way it implements the and/or relation between predicates. At each level the rules are combined and the model can find more complex dependencies.

Notice also that the model implements reductions and expansion on rules. With expansion you consider that a relation like “moveable(x)” can implicitly be thought as “for all y it is moveable(x,y)”. Reduction is the opposite, when you loose one arity in a relation and you compute it in the sense of “exists at least one” or “for all”.

The model can combine together relations with different arities, and consider also the “exists” and “for all” quantifiers. The more times you allow to do this composition, the more complex rules you can compute. You may have noticed that tensors are in the form of [m,m-1,r] and you may wonder how you can consider a relation like relation(x,x); well you will have to deal with relation(x, y!=x) and relationSymmetric(x), so two relations to implement it but NLM can still handle it. I really invite you to read the full articles if you want to understand how the process is done, because it is very clear but requires some pages to be explained.

Once trained on few possible input object, the NLM can scale to an higher number of inputs: this because the relations are ariti based and scaling them to more object just requires to apply the same model to an higher number of permutations. This is a great property: a model trained on 20 instances can scale to 100 instances – but due to the factorial they cannot scale to huge numbers.

The paper evaluates NLM performances with the block world problem, and also with the family tree problem (who is father or x, who is the maternal uncle of x). NLM are able to learn rules that allow to reach 100% success, but they have to be trained with curriculum learning and for some problems more seeds have to be used because the problems are complex and it is not guaranteed to find a model that graduates in complex classes.

If you want to see NLM in action, visit theirs page on Google: https://sites.google.com/view/neural-logic-machines, it is nice to see that this model is able to learn the rules needed to sort an array, find the shortest path in a graph or execute the block world with many objects.

Neuro-Symbolic AI: three examples

Some weeks ago I posted the neuro-symbolic concept learner article, and I wanted to know more about this approach. I then read about GRUs, used in that system, and this week it has been the time to learn about Neuro-Symbolic AI in general. I read

Neuro-Symbolic AI: An Emerging Class of AI Workloads and their Characterization. Zachary Susskind, Bryce Arden, Lizy K. John, Patrick Stockton, Eugene B. John

https://arxiv.org/abs/2109.06133

The question behind the article is: “are this new class of AI workloads much different from neural network/deep learning models?”. The authors first provided 3 references to Neuro-Symbolic systems, and then they investigated theirs performances. Theirs first finding is that the symbolic part of the computation is much less parallelizable than the neural network one: the symbolic part requires operations on few parameters and has a complex control flow that is not suitable to run on a GPU. Fortunately the symbolic part is not the one that dominates the response time of those systems. The symbolic part manipulates the features extracted by the neural part, and this is the reason why neuro-symbolic systems are more explainable: it is much easier to understand how the output is decided. This implies that these are really composite systems: one or multiple neural networks focus on some task, while the symbolic part reuses theirs output and focus on providing the output. Another advantage is that Neuro-Symbolic systems can be trained with less samples that pure neural ones.

It is now better to introduce the 3 systems under examination. The Neuro-Symbolic Concept Learner (NSCL) is the same system I described few weeks ago: its goal is to observe an image with many solids of different shapes and color and answer questions like “is the green cube of the same material of the sphere?”. The Neuro-Symbolic Dynamic Reasoning (NSDR) system answers to a much more challenging task: observe a 5 second video where solids moves, collides, or exit the scene and answer a natural language question like “what caused the sphere and the cylinder collide?”. The third example is the Neural Logic Machines (NLM); it is quite different from the previous two because there is no separation between the symbolic and the neural part, even though they are able to perform inductive learning and logic reasoning. NLM are for instance able to solve Block World tasks, given a world representation and a set of rules, decide the actions needed to reach the desired final state. The description provided was quite vague, for this reason I plan to read the referenced paper in the next weeks.

The NSCL is composed of a neural image parser extracting the objects positions and features, a neural question parser processing the input question (using GRU) and a symbolic executor that processes the information and provide the final answer. The NSDR is composed of a neural Video Frame Parser segmenting the images into objects, a dynamic predictor that learns the physics rules needed to predict what will happen to objects colliding, a question parser and a symbolic executor. The symbolic executor in NSCL works in a probabilistic way, it is so possible to train it as neural networks; this is not true for the NSDR where it is a symbolic program and runs only on a CPU really as a separate sub-module.

To pursue theirs goal the authors had to profile these systems, and it has not been always easy to set them up. For this reason they decided to completely replace some components with some others more manageable. This gives an interesting list of modules that can be reused:

Detectron2 is a frame parser that extracts objects position, shape, material, size, color… OpenNMT is a question parser able to translate a natural-language question into a set of tokens, PropNet is a dynamic predictor able to predict collision between objects that may enter and leave the scene.

The paper also describe an useful concept I missed, the computational intensity. Suppose you have to multiply an m*k matrix for a k*n one. in this case the number of operations will be O(mkn), because of the way the algorithm works. By converse the memory needed will be O(mk+kn+mn) so you obtain:

When you multiply big nearly square matrices you have an high intensitiy, and it is more easy to parallelize the work. By converse if you have matrices with some dimension very small (or even vectors) the intensity will be low and parallelization will be more difficult to introduce. The paper explains why the more symbolic parts of the computation are low intensity and difficult or impossible to parallelize with a GPU; luckily their execution does not require as much time as the parallelizable part.

Now I have some more interesting links to investigate, and I will start from NLM.

Again on Gated Recurrent Units (GRU)

The article and the explanations I found last week were quite clear, but I wanted to read the paper that introduced GRU:

Kyunghyun Cho, Bart van Merriënboer, Dzmitry Bahdanau, and Yoshua Bengio. 2014. On the Properties of Neural Machine Translation: Encoder–Decoder Approaches. In Proceedings of SSST-8, Eighth Workshop on Syntax, Semantics and Structure in Statistical Translation, pages 103–111, Doha, Qatar. Association for Computational Linguistics.

I was expecting to see a paper telling all the good things a GRU can do, but I was quite surprised to see a paper on automatic language translation. The GRU has been introduced in that context, and then it has become a useful tool in many other scenarios.

It has been a good opportunity to learn something about automatic language translations, at least how it was done 10 years ago. At that moment the most effective way of doing translation was using Statistical Machine Translation (SMT): these systems need tens of gigabytes of memory to hold the language models. In the paper a neural approach was instead used: neural networks can learn how to map a phrase from language A to language B. According to the authors, the memory required by the neural models is much smaller than that SMT requires. The neuro-translation approach was not introduced in this paper, but by some other authors a couple of years before.

The translation works in this way: you have as input a sequence of words in a source language (English). The input phrase has a variable length, but it ends with a dot or a question mark, etc. A neuro-encoder module maps this phrase to a fixed-length representation, a vector of size d. This vector is used by a neuro-decoder module that maps it to a sequence of words in the target language (French). It’s like all the possible knowledge in a phrase could be mapped onto a finite set of variables z_i…z_d and this vector could be universal to all the languages: a fascinating idea! Of course, if the d size is small the machine will not be able to work with long and complex phrases. This is what the authors have found: the translators are quite good with 10 to 20 word phrases, then the performances start to decrease. Also, whenever the machine encounters a new word it does not know, it will not be able to produce a good translation. The machine has to be trained with pairs of phases in the source and target languages, therefore new words are a problem.

Luckily for English and French speakers, there are good corpora that can be used to train the neural networks: I hardly doubt it would be possible to train in this way a German to Greek model, or whichever other pair of European languages excluding English. This is just another example of cultural bias in AI.

Another interesting aspect is how to evaluate the translation quality: a method called BLEU is the standard in this field. I had a quick look at “understand the BLEU Score“, from Google Cloud documentation. You need to have a source phrase and a reference translation, then the candidate translation is compared to the target phrase searching single words, pair of words, up to groups of 4 words. The groups must appear both in the candidate and in the reference phrase; there is also a penalty if the candidate translation is too short. An understandable translation should have a score of 30 to 40, a good one is above 40. The results in the paper score about 30, when the phrases are not too long.

Coming back to the paper, they actually introduce “Gated Recursive Convolutional Neural Network”: so there are gated units as I expected, but I did not expect to see them composed into convolutional networks. There are two reasons for this: the first one is that the input phrases have variable lengths, and to handle this the GRU units are composed in a sort of pyramid. The second one is that convolutional networks share the same parameters in the units, reducing drastically the number of parameters to be learned. Citing the authors “…another natural approach to dealing with variable-length sequences is to use a recursive convolutional neural network where the parameters at each level are shared through the whole network (see Fig. 2 (a)).” In the picture below you can see an example of how the GRU are laid out:

Another interesting aspect is that in the paper the GRU units have a left and right input, the left word and the right word. The hidden state h (or c as cell state) is updated by choosing from the left input, or the right input, or it is reset to a combination of the 2.

The coefficients in the first equation are normalized so that the next c state depends mostly on one of the 3 terms. The j coefficient is a positional counter left to right, the t coefficient is as usual the time evolution.

As you can see in the pyramid example above, some lines between the GRU units are missing: their W coefficients are too low with the current input, and that contribution is not taken into account. In a certain way, the structure is parsing the phrase “Obama is the President of the United States.” as “<Obama, <is the President, of the United States.>>”. The structure has been derived uniquely from the training, and nothing has been done to instruct the system about English grammar! Very remarkable.

In the paper nothing is said about the decoder unit, so I don’t know if it just a plain neural network or a recurrent one. In the end the state vector Z should represent the phrase meaning, and there should be no need of recur on the previous state.

Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) vs Long short-term memory (LSTM)

The paper on neuro-symbolic learning contained a reference to Gated Recurrent Units: this week I decided to understand more about them and see how they differs from LSTM. First of all you can think at using GRU or LTSM when your problem requires to remember a state for a period of time: for instance, in text analysis, predict the use of masculine/feminine or singular/plural forms; in a phrase there must be accordance of with the subject (she writes every day/they write every day).

Both the units are recurrent, at each input step they carry on a piece of information; but LSTM is by far more complex than GRU. The models equations are expressed with a different symbology, it has taken me time to adapt them to be able to do a comparison.

Let’s c be the recurrent state that will be carried on when time passes, and x be the input of a cell. Of course you may have many inputs, and many states: you must think at these variables as vectors and not just scalars. To express the formulas I will use also W as weights for the input variable x, R as weights for the c state, and b as biases – also these are vectors.

There is simplified version of GRU that has these equations:

A forget variable f is computed using the current input and the previous cell state. Here sigma is the sigmoid function, we want to have it always near 0 or near 1. When it is near 1 the cell must forget its state, for instance a new phrase begins ad you need to forget the previous subject number.

c hat stands for the future candidate cell state, and is computed using the current input, the previous cell state (but only if you must forget the previous state) and this time it is passed trough tanh to be between -1 and 1.

c the true next state is computed in this way, if I need not to forget f is near zero, so I keep the previous c.If I need to forget, I take the new candidate state c hat.

GRU learns when is the case to forget the state, otherwise they remember even for long time what happened before.

There is a more complex version of GRU that has two distinct variables, reset and update:

Should be easier now to decript it; if not there is a great video from Andrew Ng that explains very well how GRU works.

Let’s now have a look at LSTM

As you see there are many more concepts: the LTSM cell has also an output variable y, z block input and f forget rules the way the cell state is updated. The output and the cell state have to be carried on to the next computation step. Does this complexity pay’s its price? Seems sometime yes and sometimes no… but LTSM will be slower to be trained as they require much more coefficients.

About GRU and LSTM comparison I have found this article:

Mario Toledo and Marcelo Rezende. 2020. Comparison of LSTM, GRU and

Hybrid Architectures for usage of Deep Learning on Recommendation

Systems. In 2020 The 4th International Conference on Advances in Artificial

Intelligence (ICAAI 2020), October 09–11, 2020, London, United Kingdom. ACM,

New York, NY, USA, 7 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3441417.3441422

The problems the authors are approaching is what to recommend to an e-commerce site user when you do not have yet information on which products they like – the cold start problem. The have taken a set of page navigations (20 million pages) on a Chinese web site and trained GRU and LSTM models to predict which products will be interesting for the user.

Some cited studies report GRU training to be 20-30% faster, and the performance higher than LSTM. On theirs side the authors trained GRU and LSTM with 128 cells and using different hyper-parameters (the optimizer, batch size…). They did not find a great difference in training times, but generally GRU perform better in theirs case. The most influential hyper-parameter was the optimizer: better to use RMSProp for them.

World Artificial Intelligence Cannes Festival WAICF

This week the WAICF has been held in Cannes: it has been 3 days marathon, with many expositors and a lot of presentations. The very good new was that it was possible to register for free, with some limitations; I have been then able to attend part of the presentations and visit many stands without having to pay for a ticket. There have been so many presentations that my brain oveflowed, and it is very difficult to report all the things I saw.

In general most of the presentation have cited ChatGPT at least few times: ChatGPT has contributed to change the way people look to AI. Before it, AI was far from people imagination: now most of us have realized that AI is here to stay and that it will have a real impact on hour lives. Of course not all that glitters is gold, and despite a lot of limitations, people start thinking at AI positive or negative implications on our lives.

There is the concrete fear that AI algorithm will be used against common people interests: many will lose their jobs because “intelligent” machine can replace them, also creative jobs that everybody believed not automatable. For instance, in a game development company, many creative artists and developers have reported they fear what AI can do to them: stable diffusion can quickly generate many impressive images, and ChatGPT can spot many bugs in source code… But this is not the only source of concern: AI is already applied in many services and can be easily used to take advantage of the customers. Is the recommended hotel just the one that optimize the web site profit, is some sort of bias introduced because you have been identified as belonging to a user group that can pay more the same service? For instance an algorithm, for a female audience, could increase lipstick prices and reduce drill prices – in the end the averages prices could be equitable, but it is just cheating.

The ethical problem was approached in many presentations. Somebody can be interested in visiting the AI for food site or Omdena: if AI can be used for bad purposes, it is also true that you can use it to do great things like United Nations projects, promote gender equality or predict cardiac arrests.

In his talk Luc JULIA, chief scientific officer of Renault, was comparing AI to an hammer: you can use it for good purposes – put a nail in a wall, bad purposes – hit your noisy neighbor, but there is a very important thing: the hammer has an handle. Its our responsibility to hold the handle and decide what we want to do with it. My consideration, it is quite unfair if holding the handle are just big companies – hence the need of some sort of regulation.

How to regulate by law AI usage? What should be encouraged, what should be forbidden, and how a customer can fight with a big company if they have been somehow been damaged? Proving that a system is discriminatory requires a lot of effort on the offended part: sample the system behavior, identify in which context it is unfair, demonstrate that the damage is not marginal but it is worth a judge attention… Creating a new law also can take years and the evolution in this domain is so fast that there is a concrete risk the law is born already obsolete. Not the same level of regulation must be applied everywhere: an autonomous vehicle requires much stricter regulation than a recommender system, of course. The legislator has to choose the right tool, just a recommendation, some incentives if some behavior are respected, or fines in other cases.

Coming back to the hammer metaphor, how good is the tool that we have? Stuart Russel, from Berkeley University, did a speak on General Artificial Intelligence, reporting many cases where it is possible to make ChatGPT or other systems fail just because they don’t really understand the meaning behind questions. For instance one reporter (Guardian) asked a simple logic question about having 20 dollars and giving 10 to a friend, asking how many dollars were there in total: according to ChatGPT there were 30 dollars. There are new paradigm that we can explore in future to build better systems like “probabilistic programming” and assistance games theory. The last one is very fascinating: what is the risk of having machines take control over the hammer handle, as they can evolve so fast and accumulate a level of knowledge no human can achieve? A wrongly specified objective can lead to disaster, but in assistance games the machine is just there to help their master and does not know its own real goal: so it just try to help and not to interfere too much.

Another subject of interest was the bias: we are training AI systems with real data. These systems are built trying to optimize some function, for instance a classifier is trained to assign a class to a sample in the same way it happens in reality; but what if reality is unfair? We all know women’s salaries are lower that men’s, we definitely do not want that AI systems perpetrate the same injustice when used in production. Nobody has today a solution for this, and it is indeed a good business opportunity. No company wants to have a bad reputation because they applied a discrimination, and few companies have the capacity of developing themselves a bias filtering. As AI will be democratize there will be the need of standard bias cleaning application, in many contexts.

The same applies to general AI models: AI is being democratized, some companies or organizations will be able to craft complex models, all the others will in the end buy something precooked and apply it in theirs applications. A real AI project requires a lot of effort in many phases: data collection, data verification, feature extraction, training, resource management (training require complex infrastructures), monitoring. This is the reason all the IT players are focusing on creating AI platforms were customers will be able to implement theirs model (SAS Viya, Azure machine learning, IBM Watson…)

Another issue with bias is the cultural bias: chat GPT is trained on English contents, but not everybody is a fluent English speaker. Which solutions exists for other languages? Aleph Alpha was presenting their model working on multiple languages (German, French, Italian…). One interesting thing I saw is that it does a big effort in trustability; the presenter showed it was possible to identify why an answer has been chosen in the source text used for training. One can decide if the answer was just randomly correct, or if it was correct for a good reason. Theirs system is also multi-modal, you can index together text and images, and text is extracted also from the images: nearly all documents have both so it is interesting to have one system that can work on that.

Trust is a word that was often used in the presentations. If we start having AI algorithms applied in reality, we want them to be somehow glass-box algorithms. A regulator must be able to inspect it, when needed, to understand if something illegal has been done (for instance penalize employees that have taken too many sickness leave days). The company that is developing it must understand how much it is reliable, and if it is using the information we expect it to use: if a classifier is deciding a picture represents an airplane just because there is a lot of blue sky, well it is not a good tool. We also must be sure that personal or restricted information do not leak into an AI model, that then is reused without our permission, or with a purpose we do not approve: our personal information is an invaluable asset.

The Credit Mutuel bank is developing many project with AI, what they reported is interesting: they conducted some experiments in humans evaluating a task alone, AI alone on the same task, and then 2 other scenarios where humans could decide if to use AI, or where they were forced to se AI propositions. The most successful scenario was the last one: the AI hammer is useful and we need to realize that it is here to stay. We also need to understand who is accountable of an AI system: people have to know what they can do and what they cannot do with AI, and this must clear and homogeneous inside the same company. When you have multiple project you realize that you need a company policy on AI. Somebody from Graphcore also suggest to focus AI projects on domains where the cost of error is low: use AI to automate writing summaries from long documents is much less dangerous than developing an airplane autopilot. they are just two different planets in term of accountability.

To conclude I would like also to cite Patricia REYNAUD-BOURET work on simulating how the human brain is working. She is a mathematician, working on simulating real neuron work: she described us how neuron works, that it is important how many stimuli are received in a time range, and this makes one neuron be activated and propagate a signal to other neurons. We have about 10^11 neurons in our brain, but is it possible to simulate theirs activity on a computer, maybe even a laptop? With some mathematical assumption it is possible to do something at least for specific brain area. This and similar work will be useful to understand maladies like epilepsy… We should all remember that pure research is something we need to foster, because in the end it will unlock incredible results.

The Neuro-Symbolic Concept Learner

Reading the Explainable AI paper I have found a reference to Neuro-Symbolic approach: extracting and working with symbols would indeed make neural network predictions human interpretable. One referred article was about answering questions on still life simplified scenes using neural networks; for instance “is the yellow cube of the same material of the red cylinder?”.

You see above a picture taken from the CLEVR dataset project. They provide images with simple geometric object paired with questions and answers, to enable ML models benchmarking. The shapes used and the questions structure is on purpose limited and well defined, to make the problem approachable.

Having been exposed, long time ago, to languages like Prolog and Clips I was expecting some mix of neural networks and symbolic programs to answer the questions: they were in my mind quite complementary. Symbolic programming to analyze the question and evaluate its result, neural networks to extract the scene features… but I was wrong, in the following paper all is done in a much more neural-network way

Jiayuan Mao, Chuang Gan, Pushmeet Kohli, Joshua B. Tenenbaum, Jiajun Wu. THE NEURO-SYMBOLIC CONCEPT LEARNER: INTERPRETING SCENES, WORDS, AND SENTENCES FROM NATURAL SUPERVISION. ICLR 2019

http://nscl.csail.mit.edu/

The neuro-symbolic concept learner (NSCL) is composed of 3 modules, a neural perception module that extracts latent features from the scene, a semantic parser that analyze the questions and a program executor that provides the answer. What surprised me, and I am still not clear on how it works, is that all the modules are implemented with neural networks and is therefore possible to train them in the neural network way. Citing the authors:

…We propose the neuro-symbolic concept learner (NS-CL), which jointly learns

visual perception, words, and semantic language parsing from images and question-answer pairs.

Starting from an image perception module pre-trained on the CLEVR dataset, the other modules are trained in a “curricular way”: the training set is structured so that in a first phase only simple questions are proposed, and in later steps things get more complicated. First questions on object level concepts like color and shape, then relational question such as “how many object are left of the red cube”, etc.

The visual perception module extracts concepts like in the following picture taken from the paper:

Relations between objects are encoded in a similar way. Each property will be a probabilistic value, of being a cube, of being red of being above the sphere… Having this probabilistic representation is possible to construct a program that use the probabilities to compute the result. For instance you can define a filter operation that filters all the cube objects, just selecting the object that have high probability of being a cube and discarding the others. The coefficients of this filter operation will be learned from the training data set.

A question will be decomposed in a sequence of operations like: Query(“color”, Filter(“cube”,Relation(“left”,Filter(“sphere”, scene)))) -> tell me the color of the cube left to the sphere. All the operation works with probabilities and concepts embedding.

It is not clear to me how the parsing and the execution works, the authors say they used bidirectional GRU for that. Also the parser is trained from the questions, in my understanding generating parse trees and discarding those that executed do not lead to the correct answer. This part is too short in the paper, I will try to dig more into this in future. I feel also missing some examples on how the features are represented.

Anyway, as the execution is decomposed in stages have a symbolic meaning (filter, relation,…), it is easy to understand “why” the ML has chosen an answer. If that answer is not correct you can look backward in the execution and see if the attribute extraction was wrong or the problem comes from some other stage. Much more XAI oriented than a simple neural network. There are a lot of interesting references to have a look to in this article, I will try to dig further.

Explainable AI (XAI): Core Ideas, Techniques, and Solutions

Looking for new ideas I have found an interesting ACM Journal, CSUR ACM Computing Surveys, which publishes surveys helpful to get introduced to new subjects; a place to have a look at from times to time. Browsing the latest issue I have found this article:

Rudresh Dwivedi, Devam Dave, Het Naik, Smiti Singhal, Rana Omer, Pankesh Patel, Bin Qian, Zhenyu Wen,

Tejal Shah, Graham Morgan, and Rajiv Ranjan. 2023. Explainable AI (XAI): Core Ideas, Techniques, and Solutions.

ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 9, Article 194 (January 2023), 33 pages.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3561048

It’s quite long, 30 pages, and it describes many techniques and tools useful to understand ML models; for instance LIME and SHAP graphs are explained, with some examples, and this will help me better understanding many other papers.

XAI is helpful in two contexts: when you are developing a model it will help you understanding if it is precise enough and if it can be used as intended, when the model is deployed, XAI will help you explaining why a decision has been taken. The understanding consists in identifying the most important features, theirs relations, the presence of bias in the training data etc.

There are many XAI techniques, they can be divided in many ways. You have model agnostic and model specific techniques, if they target or not a specific model. You have global interpretation or local interpretation depending if the technique tries to explain in general what the model is doing, or it is limited to explain why a decision has been taken for a specific input.

The paper has many sections, the ones I liked the most are “Feature Importance” and “Example-Based Techniques”, but there are other sections about tools for model explainability (Arize AI, AIF360, AIX360, InterpretML, Amazon SageMaker, and Fairlearn) and distributed learning.

To understand features, you can use the Permutation importance technique: it is computational expensive but it’s output is a nice table with a number for each feature, the higher the value the more important the feature is. You have also PDP Partial Dependence Plots, whose output is a graph. On the x-axis one feature, and a line with the predicted value, around the line a confidence area. This technique analyzes a feature at the time, and does not take into account correlations.

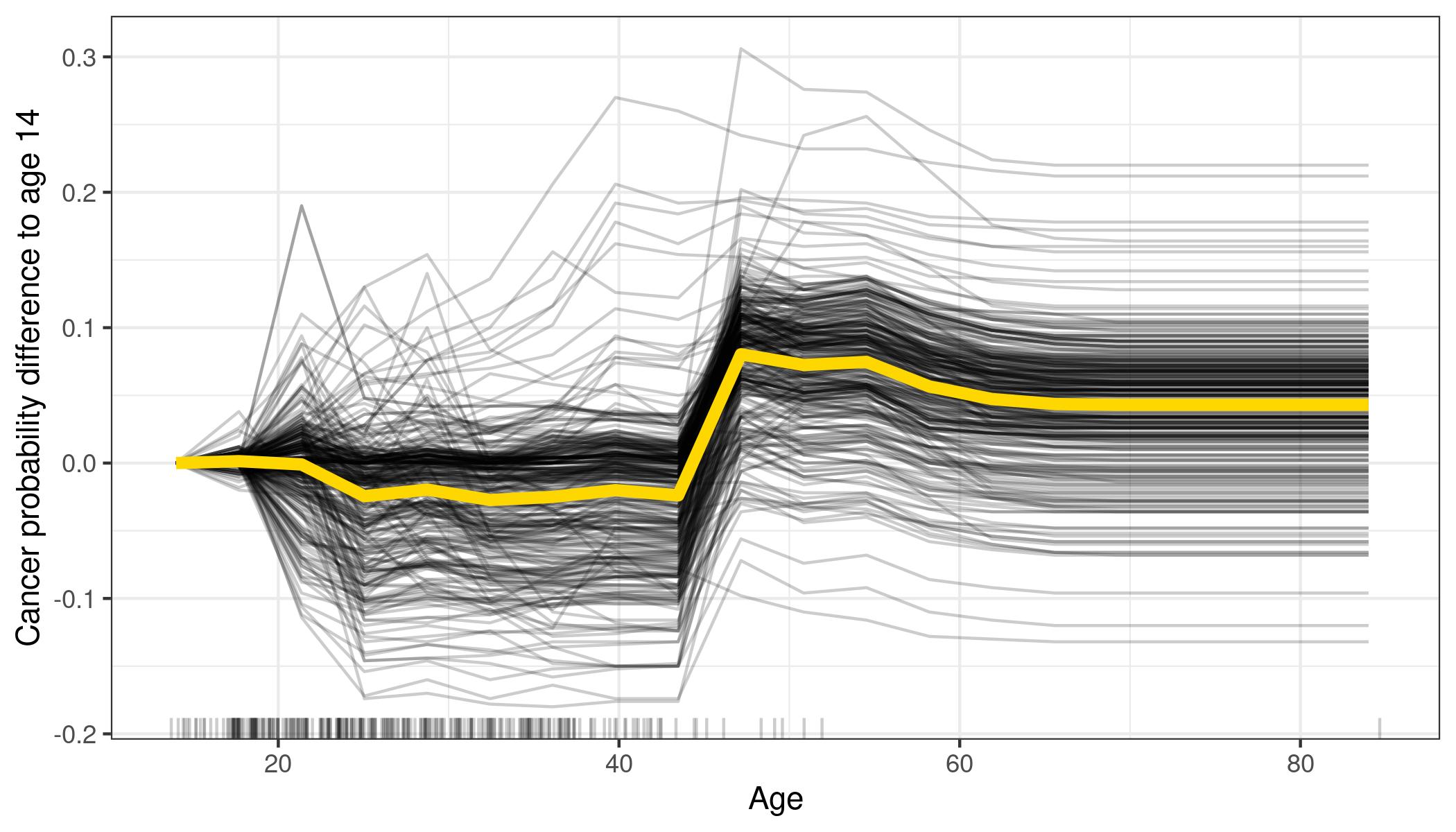

ICE Individual Conditional Expectation plots are very similar to PDP, instead of seeing a gray area around the line, you will see many lines showing what is happening for various instances. Of course if you plot too many instances you will have something difficult or impossible to read, but it is more easier that interpret than the gray area in PDPs.

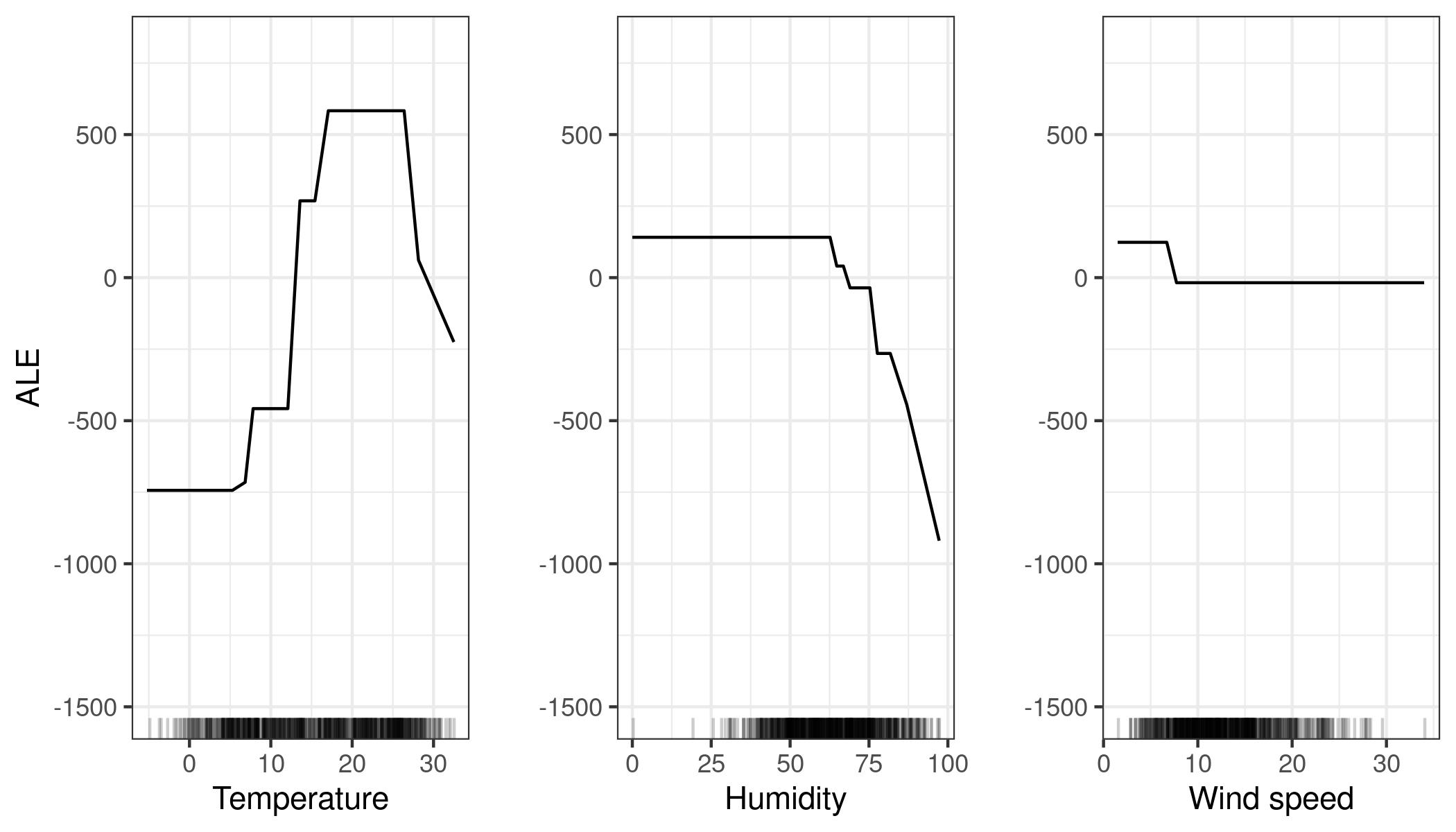

ALE Accumulated Local Effects are another way to visualize features importance: the authors do not explain much about them, they just say that the work also well if features are correlated. Below you see an example about bike rentals, it is easy to understand when a feature becomes important: when is raining (high humidity) people do not want to rent a bike.

Moving to local interpretation, you have the LIME Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations technique: a sample input is perturbed and the impact on the prediction is captured. With images it is really easy to understand which elements the model is taking into account to make a prediction

Lime can work in other contexts than images, showing which feature values are increasing (or decreasing) the prediction

Another great tool to visualize feature importance is SHAP:

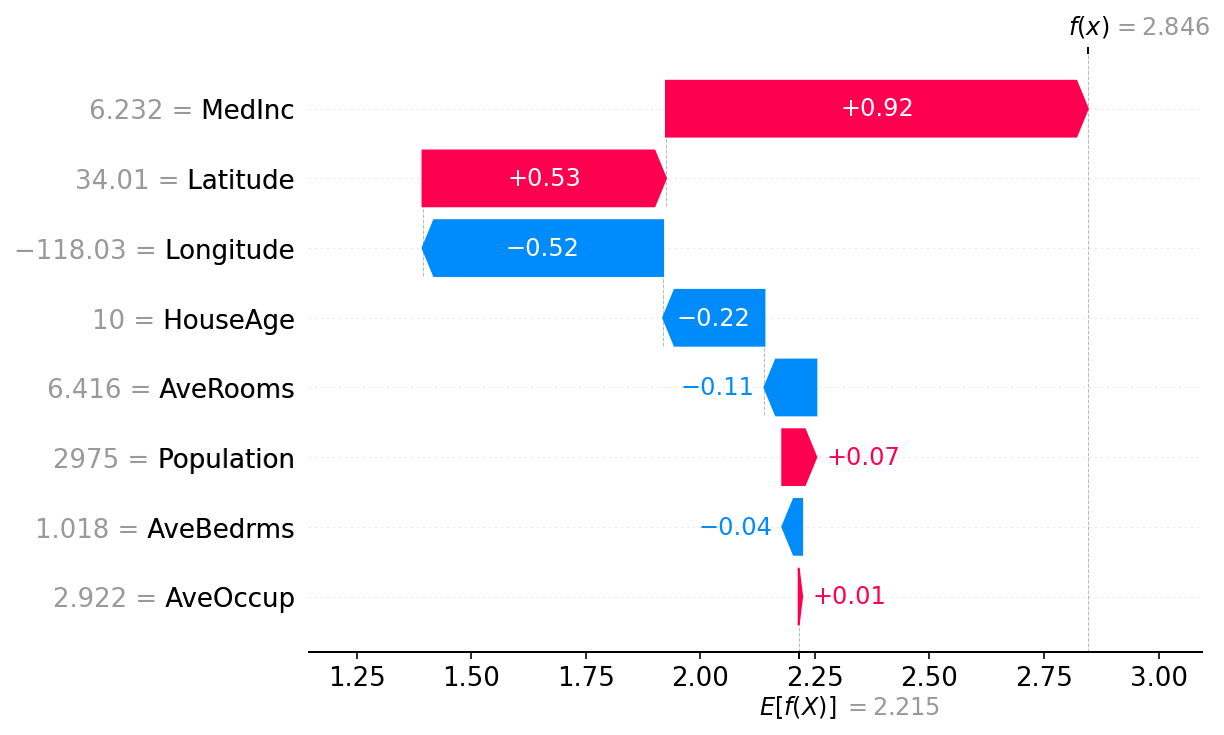

Here features are sorted by theirs impact, Feature 1 has more impact than Feature 0. When the bar is red painted, that value will make the prediction increase, when it is blue it will make the prediction decrease. Shap output can also be represented in this way:

Here you see how each feature has contributed to the final result, starting from the average model prediction. AveOccup and AveBedrms have nearly no impact, Populations contributes to the house price a bit more, AveRooms decrease it, etc until MedInc that contributed the most, and the final prediction is 2.846. Each observation will have its own SHAP diagram.

Another interesting question you can ask is “what is the minimum change of a feature that can make the model prediction change?” An interesting question for a classifier model. These are called Counterfactual Explanations, usually presented in tables that shows the features values compared to the original sample.

This paper presents a plethora of useful techniques, and references many tools to apply them: it is definitively a good bookmark to add to your browser.

Trustworthy AI

When can we say that a AI/ML product is trustworthy? This paper authors propose us to analyze it from six different point of view: safety and robustness, explainability, non-discrimination and fairness, privacy, accountability and auditability, environment friendliness. If you are interested, you will find in the paper many examples, references to other articles and tools, and a rich bibliography.

Haochen Liu, Yiqi Wang, Wenqi Fan, Xiaorui Liu, Yaxin Li, Shaili Jain, Yunhao Liu, Anil Jain, and Jiliang

Tang. 2022. Trustworthy AI: A Computational Perspective. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 14, 1, Article 4

(November 2022), 59 pages.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3546872

We are already using many AI application in our day by day life: to unlock a phone, to ask to play a song, find a product in an ecommerce web site, etc. but can we really trust these systems?

From the “safety and robustness” point of view, you would like that the ML system works in a reliable way, even if some input perturbations occurs; this is especially true for applications that can put humans in danger, like autonomous driving. But this should not stop at natural “input perturbations”, we should also take into account that somebody can will to fool the system to take advantages. Think at a recommendation system, if the attacker can fool it making it suggest what they wants, they can sell this to somebody and take profit of this activity. Consider also that many times ML systems are trained with data crawled from internet, so it is not such a remote possibility that somebody starts seeding poisoned data to have some profit. These are kind of black box attacks, the more the opponent has access to the internal of the ML, the more they can do: for instance craft exactly the kind of noise to add to the input data to obtain from the system the prediction they want. There are some techniques to protect the system, like craft another model that validates training input, telling if they are legitimate or adversarial… but does not seems an easy task. The authors cites these tools that can be useful: Cleverhans, Advertorch, DeepRobust, and RobustBench.

The picture below, from Cornell University, show a famous input example that can fool an AI system. You can have a look at https://spectrum.ieee.org/slight-street-sign-modifications-can-fool-machine-learning-algorithms if you are interested.

In real life, I bought a car with a lane assistant device, the car should advise you if you accidentally cross a line without using the turn signal: the steering wheel becomes hard and the car stays in the lane. This is perfect on the highway, but when I drive in the country side it detects the lanes but not other obstacles like branches fallen on the road, or even bikes! Not trustworthy enough, and it is very unpleasant when you have to turn and the car doesn’t want to!

From the “non discriminatory and fairness” point of view, with AI you get what you train: if you train a loan approval system with data that favor white Caucasian people, you will get an unfair system that discriminates other ethnic groups. The same if you train a chatbot with un-proper language, you will have a lot of complains because of sexual or racist language (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tay_(bot)). An AI system should not be biased toward a certain group of individuals.

The bias can come from many sources: unexperienced annotators preparing the training data set, some improper cleaning procedure, some data enrichment algorithm. Sometimes even if the ethnic group is not explicit in the training data, the algorithm will be able to deduce it. Ideally we would like to have all ethnic group treated in the same way, but this sometimes enters into conflict with the model performance, just because the bias exists in real world. The authors refers to more that 40 works about biased AI in many domains: image analysis, language processing, audio recognition, etc.

To be trustworthy a system should also be “explainable“, especially if their domain is heath care or autonomous driving. It should be possible to get one idea on how the system works in general, and this is actually possible with some algorithms: decision trees are easy to understand an the humans can also adjust what is done. This is not always possible, in this case maybe it is possible to have an explanation for a specific input sample. For instance the system may be an image classifier: you provide a picture and you get an indication of which pixel areas are the most relevant for the classification, an heat map on the image. A famous example of this is LIME Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (see https://homes.cs.washington.edu/~marcotcr/blog/lime/ )

The authors provides a list of tools to explore about explainability: AIX360 (AI Explainability 360), InterpretML, DeepExplain and DIC.

Also from the training data comes a “privacy” issue: is it possible, from the model output, to deduce the data used during the training, in this way getting back to information that should not be disclosed? There are 3 approaches to this problem: confidential computing, federated learning, and differential privacy. Confidential computing tries to use devices that are not possible to disclose or operate from outside the training environment, or using homomorphic encryption. Federated computing compute a ML exchanging between parties only parameters, and not the training data: in this way the original data do not exist the boundary of the single entity training the model. Notice also that it is possible to introduce white noise in the parameters exchanges, to be more safe. Differential Privacy aims to provide statistical guarantees for reducing the disclosure about individual introducing some level of uncertainty through randomization.

I did not find the part on auditability much interesting, and I preferred having a look at the “environmental and well-being” section. Actually training some AI models produce the same carbon emission than a human living 7 years! Some other models produce more emission than a car in its lifetime! (Emma Strubell, Ananya Ganesh, and Andrew McCallum. 2019. Energy and policy considerations for deep learning in NLP. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.02243 2019)

How to reduce this huge consumption? Among the possible techniques there is model compression – reducing the model size will sacrifice some performance, not so much if the model is big and overfits. Also, pruning nodes layer by layer in a neural network seems a promising approach. Specialized hardware is another way to approach the problem. Crafting energy consumption savvy AutoML models is also a good idea: AutoML tools will be more and more widespread, and their users will benefit of environment friendliness without even knowing it.

Deep Neural Decision Trees (DNDT)

Following the “machine learning algorithms in 7 days” training there was a reference to this paper:

Deep Neural Decision Trees, Yongxin Yang – Irene Garcia Morillo – Timothy M. Hospedales, 2018 ICML Workshop on Human Interpretability in Machine Learning (WHI 2018), Stockholm, Sweden.

https://arxiv.org/abs/1806.06988

Decision Trees and Neural Networks are well different model, so I was curious to understand how it was possible to do a neural network that behaves as a decision tree! With some tricks it is possible to do that, but why would you like to do such thing? The authors propose these motivations:

- Neural networks can be trained efficiently, using GPUs, but they are far from being interpretable. Making them work like decision tree results in set of rules on explanatory variables, that can be checked and understood by an human. In some domains this is important to make the model accepted.

- The neural network is capable of learning which explanatory variables are important. In the built model, it is possible to identify useless variables and remove them. In a sense the neural network learning performs a decision tree pruning.

- Implement a DNDT model in a neural network framework requires few lines of code

The DNDT model is implemented in this way: the tree will be composed of splits, corresponding to a single explanatory variable: this is a limitation, but makes very easy to interpret the results! The splits here are not binary, but n-ary: for instance if you have the variable “petal length” you can decide b_1,b_2,…,b_n coefficients that represent the decision boundaries. If the variable is less than b_1 you will follow one path in the tree, between b_1 and b_2 the second path, and so on. These boundaries will be decided by the Neural Network training algorithm, for instance the SGD.

The number of coefficients will be the same for all the explanatory variable, it is a model meta-parameter. This may seem a limitation, but actually it is not: the SGD algorithm is free to learn for instance that a variable is not important, and set all the coefficients so that just one path is followed. This is the reason why the DNDT is able to “prune” the tree: if you see that, on all the training samples, only one path is followed you know that that variable is useless.

To train the neural network with SGD this split function must be differentiable: the authors propose this soft binning function:

softmax((wx+b)/tau)

softmax function

Where w is a constant vector containing [1,2,…,nSplits+1] and b is a vector containing the split coefficients to be learned. Tau is a parameter that can be tuned, the closer it is to zero, the more the output looks like an one-hot encoding. The following one is a visual example, with tau=0.01 and 3 splits:

So far we have a function that can be applied to a single scalar explanatory variable: each input variable is connected to a unit with the soft binning function, which has n outputs, one for each decision tree node branch. All these output will be simply connected to a second layer of perceptrons, so that you map app the output combinations: the authors refers to this as a Kronecker product. So suppose you just have 2 input variables a and b, and you have n=3 splits; the two input units will have 3 output each: o_a1, o_a2, o_a3, o_b1, o_b2, o_b3. In the second layers the perceptrons will have these input pairs: [o_a1,o_b1],[o_a1,o_b2],[o_a1,o_b3],[o_a2,o_b1],[o_a2,o_b2],…To lean more about the Kronecker product you can have a look at Wikipedia.

The second layer outputs are then simply connected to a third-layer to implement the soft-max classifier. Reading the paper you will se a classifier example for the Iris data set: the input variables are petal length and petal width and the output categories are Setosa, Versicolor and Virginica.

Clearly all these all-to-all connections make the model simple but not able to scale to a large number of input variables. The authors propose as solution training a forest of decision trees, based on fewer variables, but this goes against the model interpretability.

To concluded let me cite the authors:

We introduced a neural network based tree model DNDT.

Yang, Morillo, Hospedales

It has better performance than NNs for certain tabular

datasets, while providing an interpretable decision tree.

Meanwhile compared to conventional DTs, DNDT is simpler

to implement, simultaneously searches tree structure

and parameters with SGD, and is easily GPU accelerated.